Sport is more than just how well you perform technically – it is how it makes you feel when your body and mind are in sync. Being physically active brings multiple benefits to your mental well-being, just as much as it does to your physical well-being. Almost every day we hear about the importance of mental health in sport.

In our Safe Sport Action Plan, we are committed to ensuring that all participants enjoy volleyball that is safe and beneficial to physical and mental well-being. Here are some resources to help you understand and feel supported in your mental health and wellness.

On October 10, 2023, we launched a Mental Health Toolkit to help volleyball organisations take actions to promote positive mental health and well-being. For more information, resources, and webinars click here.

WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH?

Mental health in sport is as important as physical health. But what does “mental health” mean and how does it differ from “mental health disorders” or “Mental illness”?

MENTAL HEALTH

Mental Health is a state of wellbeing in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can perform productively, and is able to make a contribution to her or his (sporting) community. Mental health is personal and subjective, and includes:

- a sense of internal well-being

- feeling in line with one’s own values and beliefs

- feeling at peace with oneself

- feeling positive and optimistic about life

From a youth’s point of view, mental health means…

- I feel like I have things to live for

- I feel that people care about me

- I feel hopeful and good about the future

- I feel in control of my life

- I’m satisfied or happy with life

- I like myself

MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS

Mental Health Disorders are clinically diagnosed conditions which produce significant and persistent changes in a person’s thinking, emotions and/or behaviours that are associated with significant distress and/or disability in social, occupational or other important activities, like learning, training or competition. Major mental illnesses include anxiety, mood, eating and psychotic disorders.

From a youth’s point of view, mental health disorders can mean some or all of the following…

- I feel sad, irritable, worried or angry a lot

- I don’t like myself

- I feel powerless, and not in control of my life

- I feel that others don’t care about me

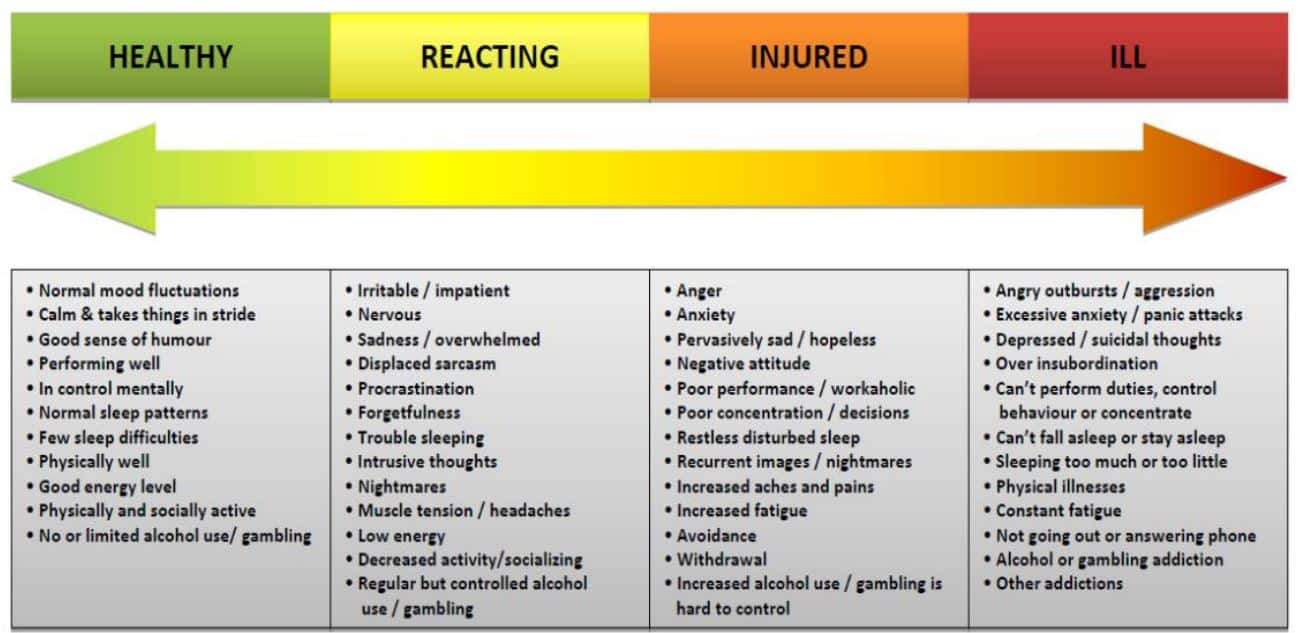

This model recognizes that mental health is not black and white. The model goes from healthy, adaptive coping (green), through mild and reversible distress (yellow), to more severe, persistent injury or impairment (orange), to clinical illnesses and disorders requiring more concentrated medical care (red).

The arrows under the four color blocks show that there can be movement in both directions along the continuum. In this way, no one is ‘written off’ simply because they are showing symptoms of an illness. It also recognises that the earlier that intervention is provided, the easier it is to return to full health and functioning (green). Therefore, it is important to improve understanding and awareness of mental health symptoms and disorders, to recognise the signs, and to create a culture that supports seeking help.

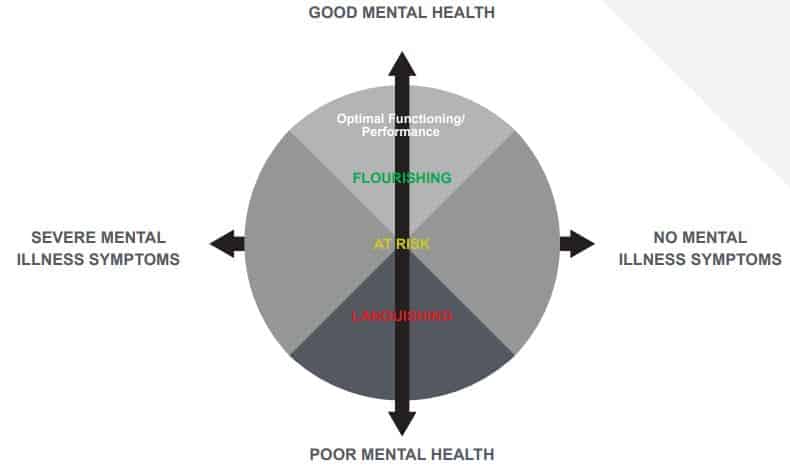

Mental health and mental illness are dynamic constructs. People’s levels of mental health and mental illness can fluctuate at any point in time across the four quadrants depicted on the left. An athlete can be mentally healthy, may have a mental health disorder, or may be in-between. Athletes experiencing a mental health disorder can recover and have periods of optimum mental health, while athletes without mental health symptoms or disorders can experience times of poor mental health, such as feeling stressed or overwhelmed.

Optimal functioning is a state of complete mental health whereby individuals are flourishing without a mental illness. However, this does not mean that people with a mental illness cannot reach optimal levels of functioning and the highest levels of performance in sport. What is most important is that individuals get the right support to achieve their performance and mental health.

key concept: mental health is a continuum

STRESSORS IN VOLLEYBALL

Playing volleyball can be an amazing way to manage stress and boost your mood. However, sport can also bring stressors that may contribute to poor mental well-being.

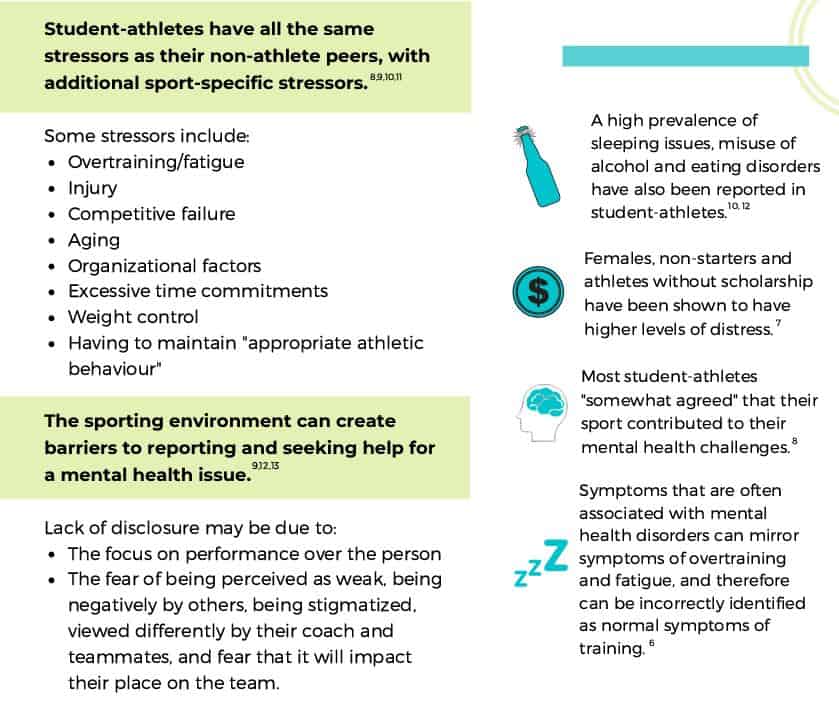

As the graphic above shows, student-athletes have been recognized as at risk of developing and struggling with mental health disorders and distress. Student-athletes are expected to balance the responsibilities of academia and athletics which creates stress. For more info visit Student Athletes Mental Health Initiative.

What are key stressors? Key stressors for participants in sport can be split into three categories: competitive stress, organisational stress and personal stress. These three categories are not exclusive and can have knock-on effects or impacts on other categories.

1. Competitive stress – these are the demands we place on ourselves to achieve competitive performance. Some of this pressure is self-imposed but pressure can also come from outside sources, most critically from coaches.

During the tournament season, performance anxiety can be a huge issue. Check out our useful handouts for how to manage these feelings. :

Players – Performance Anxiety

Coaches Handout – Performance Anxiety

Referee Handout – Stress in Tournaments

2. Personal stress – factors to do with our “non-sporting” life can bring stress, such as a challenging workload, lack of sleep, or stress at school. In last year’s Annual Survey, the top factors affecting Players’ performances in volleyball were lack of sleep and general life stress. Youth players also highlighted fear of failure while Adult players were impacted by their professional life. Coaches and Referees also ranked general life stress, lack of sleep and professional life as the top 3 factors affecting their participation in volleyball. The top factors listed by all participants were physical fatigue and mental exhaustion.

3. Organisational stress – these stressors are associated primarily with the sport organisation or team in which you belong. It may involve coaching style, team dynamics, or the sport culture. For example, the stronger your team identity or “bond”, the harder it can feel for you to express ways that you may feel differently which may in turn create stress and pressure to conform.

TIPS FOR PLAYERS

The Step UP Program has these tips for how you can speak to a team mate or friend if you notice that they are behaving differently and you are concerned about them:

Be curious/ask questions to understand from their point of view.

Ask permission if the topic is sensitive.

Avoid gossiping and rumor spreading.

Take care of yourself — it can be difficult on helpers as well.

Tell someone if you believe that the individual is in danger from themselves or from/to others.

If you or the individual are minors, find an appropriate and responsible adult to get help and support.

TIPS FOR COACHES

Volleyball organisations and coaches play an important role in creating and fostering a culture that recognises the psychological wellbeing of athletes and encourages help-seeking behaviors. Coaches can be the first point of contact for a player to express their feelings. When athletes come to you in emotional distress and they do not present an immediate threat to the safety of themselves or others:

DEMONSTRATE COMPASSION – Some helpful tips for calming the individual and demonstrating compassion are:

Remaining calm yourself — maintain calm body language and tone of voice.

Listen to the individual. Allow him/her to express his/her thoughts. Provide him/her a forum in which he/ she can be heard. It’s OK to have a moment of silence between you.

Avoid judging the individual. Provide unconditional support. You do not have to solve his/her problem. Normalize the experience and offer hope.

GATHER INFORMATION – Ask questions, including questions of safety (“Are you thinking of hurting yourself?” and “Are you thinking of suicide?”) Asking the important questions will NOT plant the idea in his/her head. By asking questions about suicide, you will receive valuable information. If he/she hesitates or confirms, you know to elevate the intervention.

Triage the severity of the situation to determine if the issue can be managed or requires professional support. Professional support should be sought in any instance when you do not feel adequately equipped to manage the situation, and when the athlete is an immediate risk to themselves and/or others.

CONNECT WITH SUPPORT – Present the individual with options for next steps. Connect the athlete to the appropriate support resources if you have them within your organisation or refer them to external organisations if needed. If the individual is a minor, contact their family or appropriate agencies.

RESPECT BOUNDARIES AND ABILITIES – Know what you’re comfortable doing and what you’re not comfortable doing. Don’t promise secrecy. If necessary, you can say, “It took courage for you to disclose this information to me. And, by telling me, it says you want to do something about what is going on. The best thing we can do is to inform someone else, such as a mental health provider, who can give you the care you need.”

DON’T FORGET THE FOLLOW UP – Once athletes have accessed the appropriate resources, coaches should engage in the following long-term support practices:

Respect and maintain the athlete’s confidentiality. These are sensitive topics and should be handled as such.

Keep the athlete engaged with the team (e.g., invite, but do not force athletes to attend practices, games, team social events, etc.).

Follow-up with the athlete on a regular basis. Be available to chat with the athlete on an as-needed basis.

Be flexible with sport-related demands, such as training times, to accommodate any needs. Be patient and sensitive to the fact that dealing with distress takes time, similar to physical injuries.

Additional Resources: Talking to Teens about Mental Health

SEEKING SUPPORT

Speak to a health professional to find out about resources and strategies to handle what you are experiencing. There are also many free, confidential, and easy-to-use resources that you can access for help and support:

- Canadian Mental Health Association

- Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport

- Headshpguys.org

- Youthspace.ca – live chat from 6pm-midnight PST.

- Kids Help Phone – Text Services: Text “CONNECT” to 686868 or Chat Services:

- Crisis Services Canada – Suicide Prevention Service: 1-833-456-4566 (available 24/7)

Consider sharing your story and experiences with your team.

Sharing your story and experiences with your team or with your coach can be a good way to educate them about mental health and destigmatize the issue. It might also help them understand how they can support you. However, sharing your story can also be a deeply personal experience. You may want to start with a select group of individuals whom you trust. This can be a good way to develop a smaller group of supporters, before opening up to the rest of the team if you feel that is needed.

When you share your experience, it’s important that you feel safe to do so. It would be advisable to ensure one or two of your trusted teammates can be there to give you support. Expect that your team may ask for ways they can help. Have some ideas about what would potentially help, and what would not be helpful (this is just as important!)

Sources and Useful Information